5 Steps For Choosing the Best Backyard Fruit Trees

This post may contain affiliate links, view our disclosure policy for details.

Learn these 5 important steps for choosing the best backyard fruit trees for your home orchard. Take the time to choose the right fruit trees to ensure that years from now you have a healthy and productive home orchard.

It all starts with the right tree. But choosing the right fruit tree can be an overwhelming task. There are so many things to consider, so much information to cross, and so many mistakes that can be made.

The thing is, fruit trees are an investment of both money and time. They are not cheap and some take years to produce so it’s important to make sure we choose the right tree.

5 Steps For Choosing the Best Backyard Fruit Trees…

Imagine planting a fruit tree and waiting three years for it to start producing only to find out that it doesn’t produce a single fruit because you should have planted another tree with it for cross-pollination. We do not what that to happen!

So let’s go over a few important things you have to consider when choosing your trees and the process of selecting the right trees for you and for your backyard so we can ensure great fruit production in the future.

Table of Content…

- Step 1 – Determine Your Growing Zone and Climate.

- Step 2 – Determine What Size of Tree You Want.

- Step 3 – Choose a Self-Pollinating or Cross-Pollinating Tree.

- Step 4 – Buying Bare Root vs. Potted Fruit Tree.

- Step 5 – Harvest Intervals and Choosing the Varieties You Want to Grow.

Step 1 – Determine Your Growing Zone and Climate…

Like all other plants, different fruit trees have different growing requirements and choosing the right tree for your growing zone play a big role in the success or failure of your fruit production.

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is based on the average minimum annual winter temperatures of an area and helps you determine which plants will grow best where you live.

Before you even start looking at fruit trees, it’s important that you know your growing zone. You can find it on the USDA website HERE. Find your growing zone by entering your zip code.

If you shop for trees at a local nursery, it’s likely that they will only have in stock trees that are known to grow well in your area (although, I did see in the past big stores like Tractor Supply sell surplus of plants from the North over here in the South, so still check). However, if you shop online or happen to be away from home while coming across a tree that you would like to bring home, you must make sure that the tree you pick is approved for your growing zone.

In order to understand a little better how trees are selected for a certain growing zone, let’s go over a few important factors…

Hardiness – is the tree’s ability to withstand and survive the coldest winter temperatures in your area. If your tree is not hardy enough you risk the chance of losing it to freezing temperatures during the winter.

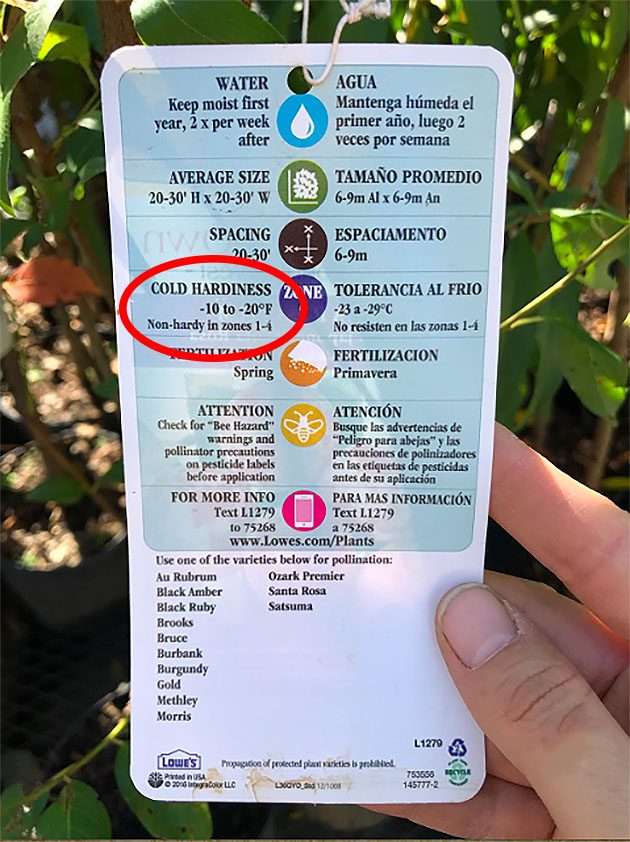

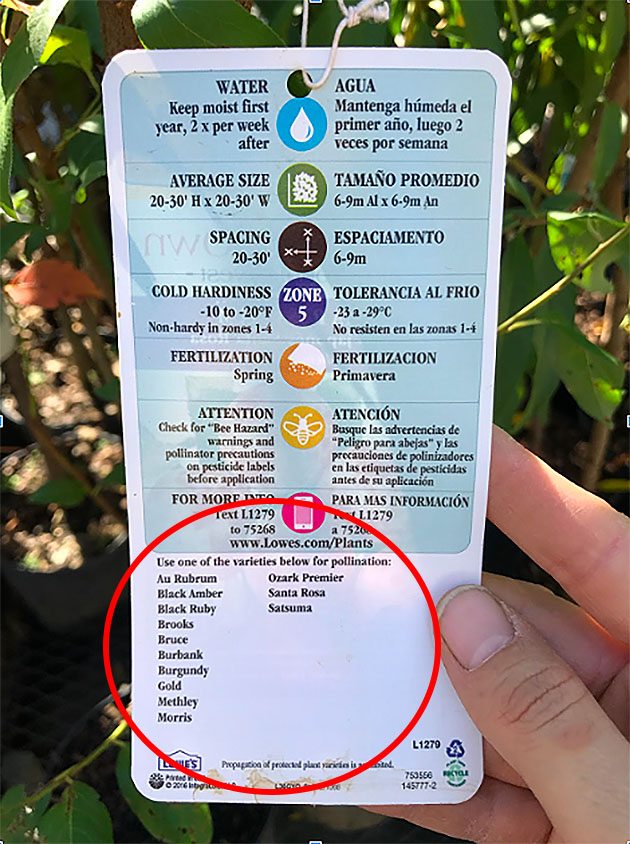

As you can see in the tag above, it says “cold hardiness -10 to -20 F non-hardy in zones 1-4”. This means the tree can survive in temperatures as low as -20F but probably not for a long period of time, this is why it is non-hardy in zones 1-4.

Most fruit trees won’t grow well in zones 1-4 so if you live in those zones you might need to find a creative solution when it comes to growing fruit trees. I’ve seen people in very cold areas grow fruit trees inside greenhouses for example. Even though they live in zone two they are able to make a zone 5 micro-climate inside the greenhouse.

Another option is to grow dwarf fruit trees in containers and roll the containers indoors during the winter (more on this later).

Take into consideration that even if the tree is hardy for your area you might still need to protect it during the winter, especially if it’s a young tree.

In NC for example, it’s hard for young fig trees to survive the winter. One way to help them is to place a wire fence around the tree and fill it with straw. Another way is to cover the tree with greenhouse plastic during a very cold spell.

Chilling Hours – deciduous plants (shrubs and trees that lose their leaves annually, usually during the fall) go dormant during the winter in order to protect themselves from the cold temperatures.

The tree has to stay dormant during the freezing temperatures but it also has to sense when it’s the right time to start growing again. It must do it late enough so the new growth doesn’t get damaged by a (late) frost and it must do it soon enough that it has enough time to fully mature and produce fruit (seed).

Trees developed an “inner clock” which tells them when it’s the right time to start growing based on the amount of what we call chilling hours.

We calculate chilling hours by counting the number of hours between 32 – 45 degrees F that an area is getting during the winter. Temperatures that are colder than 32 degrees F do not count towards chilling hours and temperatures above 45 degrees F count as half a chilling hour while warmer temperatures count as negative chilling hours.

Let’s take the Meyer Lemon tree for example. The compatible zones to grow this tree are 9 and 10. This lemon tree, like most other citrus trees prefer areas with no frost at all.

As someone who lives in zone 7b, if I wanted to grow lemons I would have to grow the tree in a container so I can bring it indoors (in the warm house) in the fall.

On the other hand, some varieties of cherry trees require 700 – 900 chilling hours in order to blossom and produce fruit. That said, you can find varieties of cherry that will need only 300 chilling hours or some that will need 500.

Trees that are labeled “low-chill” require between 250 – 400 chilling hours.

Trees that are labeled “medium-chill” require 400 – 700 chilling hours.

Trees that are labeled “high-chill” require 700 – 900 chilling hours.

Don’t worry, you don’t have to go and start counting chilling hours, if the tree is marked suitable for your growing zone, someone already did the calculation for you. However, it’s important to understand chilling hours so you can understand your tree better.

The first step in choosing the right fruit tree for your orchard is to pick a tree that is suitable for your growing zone.

Step 2 – Determine What Size of Tree You Want…

Fruit trees come in three sizes: standard, semi-dwarf, and dwarf.

Standard-size trees will mature to 18-25+ feet tall and wide (the exception will be peach and nectarine which only grow up to 15 feet which is considered their standard size). Semi-dwarf fruit trees mature to 12-15’ tall and wide. Dwarf fruit trees will mature to 8-10’ tall and wide.

It’s important to understand that the dwarfing trait does not occur in the variety of the tree but in the root stock. We are able to control the size of a tree by grafting a shoot of the desired variety onto a specific root stock. This means that the same variety of fruit tree can come in all three sizes, for example, a dwarf McIntosh apple, a semi-dwarf McIntosh apple, and a standard size McIntosh apple.

When contemplating what size of fruit tree you want to purchase, consider a few things:

How fast do you want fruit – dwarf fruit trees will bear fruit within a couple short years while standard fruit trees may take 5-7 years. Semi-dwarf might take a little longer than dwarf but not as long as standard trees.

The amount of fruit the tree will produce – Standard fruit trees will take longer to bear fruit, but once started they will produce a very large amount of fruit.

Dwarf fruit trees will produce a much smaller amount of fruit but it might be enough for a small family and you can grow more than one tree to increase fruit production.

Semi-dwarf trees will produce twice as much as dwarf trees without taking up much more space.

The amount of growing space you have – to make it easy to remember, you should space fruit trees according to their mature size. So if a tree matures to 30’ wide, you should space it 30’ apart from other trees. If a tree matures to 8’ wide you should space it 8’ from other trees.

So you can see, if you have a small space for fruit trees and you want a few trees so you have a variety of fruit you are better off choosing semi-dwarf or dwarf fruit trees.

Container growing – if, on the other hand, you have no room at all for fruit trees (let’s say you live in an apartment) but you still want to grow fruit, you can do it by growing trees in containers. In this case, you want to choose dwarf varieties.

Shade or swings – if you’re looking for a tree that will be big enough to provide shade in a certain area, or if you have this vision of a wooden swing hanging from a tall branch, you’ll need to choose a standard variety.

Semi-dwarf and dwarf fruit trees will not provide you with any shade and their branches will be much thinner than those of a standard size tree.

Safety – no ladder is required when caring for dwarf fruit trees and, most of the time, for semi-dwarf as well.

On the other hand, you would have to climb rather high if you grow a standard variety. Although, there are ways to prune standard-size fruit trees so the branches stay rather low (read here all about pruning fruit trees). But generally, if climbing is not your thing, you might want to go with dwarf or semi-dwarf trees.

Easy care – pruning, spraying, netting, thinning fruit trees, spotting disease… It takes minutes to do those things with smaller varieties of fruit trees when it might take hours to do with standard varieties.

Mobility – if you know that you are probably going to move in the near future and think that you don’t want to invest in fruit trees because you might not be around to enjoy the production in a few years, consider dwarf fruit trees. You can plant them in a container and when the time comes to move, simply move them with you!

You can read all about the benefits of growing dwarf fruit trees in an article that I wrote for The Prairie Homestead.

Length of life – dwarf fruit trees won’t live as long as standard trees. Where a standard tree will live for 35-45 years, you can expect a dwarf tree to live for 15-20 years. A semi-dwarf tree will likely fall somewhere in between.

Extreme growing conditions – since dwarf and semi-dwarf fruit trees are created by grafting on a certain root stock, you can choose a root stock that is more likely to handle your extreme growing conditions.

For example, let’s say you live in an area that experiences extreme droughts, you can have a tree custom grafted for you that produces the fruit you want and is grafted on a drought tolerant root stock. This way, you have a better chance of growing your desired variety even though you live in an area with extreme conditions.

If you consider this option try searching online for “custom grafted fruit trees” and you will find a few nurseries that will do this for you.

Multi-grafted fruit trees – grafting allows us to grow one tree that produces a few different kinds of fruit (see my grafting tutorial for more information about grafting fruit trees and learn more about grafting techniques). But those unique trees are not always available in all sizes, so if you want to go with a multi-grafted tree you might have fewer size options.

With multi-grafted fruit trees, you get one tree that produces two or more different kinds of fruit. For example, a cherry tree can produce both a deep red and golden blushed cherries.

If you have a very limited amount of space or if you just want to make things a bit more interesting, multi-grafted fruit trees are a great option. Just get ready to have long conversations with your guests!

So, the second step in choosing a fruit tree for your orchard is choosing a tree size that is best for you.

Step 3 – Choose a Self-Pollinating or Cross-Pollinating Tree…

This is a very important subject to pay attention to when choosing fruit trees and it’s completely up to you to make the right decision here.

Whereas by choosing a tree that is listed as compatible with your growing zone and conditions you can assume chilling hours and hardiness are already calculated for you, pollination is up to you to figure out.

Pollination means the transfer of pollen from the male to the female reproductive organs of a plant. This allows for fertilization and the development of fruit: a seed-bearing structure made from the ovary of the plant after flowering.

Here is the deal… Without pollination, fruit will not develop on your tree. Fruit trees are divided into two categories:

Self-pollinating – (also called self-fertile trees) are trees that do not need another tree to complete the pollination process.

Cross-pollinated – are trees that do need another variety of tree to complete the pollination process.

If you wish to grow one tree of a certain type, for example, one peach tree or one cherry tree, you must make sure that the tree you choose if self-fertile or you won’t have any fruit produced.

On the other hand, if the variety of fruit you wish to grow needs another tree for cross-pollination you need to make sure you choose the right tree to pollinate it. This is usually listed on the tag or listed in the description of the tree if you shop online.

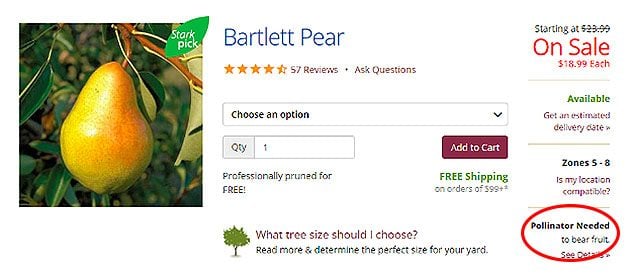

Here is a screenshot from the Stark Bro’s website (a great resource for information and a very large online fruit tree nursery).

You can see on the lower right-hand corner “Pollinator Needed”. It’s not hard to miss that. Of course, every online tree nursery will list it differently and if you buy your trees at a local nursery it will be listed on the tag. But you must remember to look for this information.

If you scroll down the sales page you most likely will find a list of recommended pollinator varieties. This means that those varieties flower at the same time as the Bartlett pear tree flowers, allowing for pollination.

You will have to choose at least one of those other trees to go with your Bartlett Pear tree in order for it to produce fruit.

Here is another example from a local nursery… This is a tag I found on a Santa Rosa Plum tree. On the bottom, you can see that it says “This fruit needs a pollinator. See back for details”.

If you flip the tag you will see a list of varieties (on the bottom) you can use to pollinate this tree. If you don’t already have one of those trees growing (or your neighbor doesn’t have one) you will have to pick one of them in addition to your Santa Rosa Plum.

If, on the other hand, the tree is self-pollinating that will be listed on the tag or online as well.

If you decide to go with a cross-pollinating tree and buy another with it to pollinate it, for best results, try to plant the trees within 50 feet from each other. This has to do with the bees, which are the main pollinator of fruit trees. We want to make sure that not only the bee can find the second tree but also that it can fly to it with no problem after collecting the pollen from the first.

Remember: it does not matter how well you care for your tree, if the tree that you planted is not self-pollinating and pollination does not happen your tree will not produce fruit. Pollination is vital for successful fruit production, so make sure you don’t skip this step when choosing a fruit tree for your orchard.

So the third step in choosing the best backyard fruit trees for your homestead is to choose between self-pollinating and cross-pollinating trees.

Step 4 – Buying Bare Root vs. Potted Fruit Tree…

If you plan on buying fruit trees locally you’re most likely to purchase a potted tree. If you plan on buying a fruit tree online you would most likely get a bare root tree shipped to you.

Here are a few things to consider:

Potted trees – a potted fruit tree probably started as a field grown tree in a large nursery. It was then dug out of the soil while still very young and shipped to another nursery. Its roots were pruned and it was then planted in a container.

The disadvantages of potted trees are that they are usually planted in very low-quality soil and fed chemical fertilizer that contains who-knows-what. Those chemical fertilizers which are planted with the tree in your orchard are most likely harmful to soil organisms.

Those trees are very often root-bound; the roots have nowhere to go and so they go around and around. This root structure is unhealthy and can affect the tree for many years even if you try to correct it at planting.

The advantages are that those trees are usually available for purchase year around and there is no rush to plant them.

Bare root fruit trees – these trees grow in living soil, or in other words, right there in the field until they are ready to be dug. Once the nursery digs them, they prune the roots and bag them.

This tree has a better root structure where the roots are spread out and not bound. Since it was grown in living soil, the roots had the opportunity to engage in a healthy relationship with fungi and beneficial bacteria in the soil. This usually results in a resilient, strong, and fibrous root system.

The disadvantage here (or is it?) is that this tree cannot be set on display. It is dug out of the field when it’s dormant and is kept in moist sawdust until sold which should be rather quickly. It then has to be planted quickly as well (although you can keep it in moist sawdust for a little while if the ground is frozen when you get it. This is called heeling. Learn more in my post about planting fruit trees).

Although it seems here that choosing to purchase a bare root fruit tree is the right decision, and it might be, it’s also nice to drive down the road to a local fruit tree nursery and talk to a local grower directly. Many times they are a wealth of information and they are very experienced in growing fruit trees locally. They most likely have in stock varieties that are known to grow very well and can take the overwhelm and pressure off of choosing the right tree on your own.

I know a few people who grow amazing fruit from potted trees they purchased locally, however, a bare root tree will most likely be stronger and healthier.

I have to note that, in the past, I’ve noticed cheap bare root fruit trees at the local Tractor Supply and other similar stores in the spring. I bought one once (it was half the price of the same tree online), and planted it and it didn’t last. I am not sure if I am correct on this, but I’ll say, this tree was probably out and about for too long before I bought it and planted it.

When you buy a bare root tree online, you can be sure that it was dug out of the field not long before it was shipped to you. When you get a container tree from a local store there is no knowing how long that tree has been on the road. It’s just something to keep in mind.

So step four is choosing bare root or a container tree.

Step 5 – Harvest Intervals and Choosing the Varieties You Want to Grow…

That’s it! It’s time to choose the kinds and varieties of fruit that you want to grow.

If you are going to plant a whole orchard, you’ll want to sit down and design your orchard first so you know how many fruit trees you can fit in the space you have. Then decide how many of which kind of fruit you want and then start digging into varieties.

When you think about varieties, think about what you are going to do with your fruit. Is it just for fresh eating or do you want to be able to preserve some of the fruit? For example, yellow peaches are more acidic than white peaches. You can can yellow flesh peaches in a simple water bath (check out my post about canning peaches), however, it has been said that it’s not safe to can white peaches. This is something to think about…

One more thing to note before you head over to the nurseries is the tree harvest interval. Some varieties of fruit trees will produce all their fruit in a matter of a few short weeks. Sometimes you’ll want to choose this kind of tree if you like to can and preserve fruit.

Other varieties production pattern will be more spread out. Those are better for fresh eating. This information will probably be listed with the information on each tree variety online. I don’t believe you can find it on a tag in a local nursery. If you shop local you may be able to get this information from the person who sells you the tree or you can Google the variety you are looking at and get the information.

Also, remember to look at the month in which the tree usually starts producing. If you plan on buying three different fruit trees it will probably be better if one is producing fruit mainly during the month of June, the other in July, and the last in August. This way you have a long season of fresh fruits.

Ok, let’s recap…

- Know your growing zone – know your zone number and understand hardiness and chill hours.

- Determine what size tree you want – dwarf, semi-dwarf, or standard size.

- Decide between a self-pollinating or a cross-pollinating tree.

- Decide if you’d like to go with bare-root or with a potted tree.

- Consider the tree harvest intervals and time of the year.

I like shopping online at Stark Bro or Grow Organic. I’ve also heard that Fast Growing Trees is a good source. Those three places have a great selection of fruit trees and a lot of great information on their websites.

Even though I like buying online, I actually prefer to make my selection by using the catalogs. It’s much easier to see all the different varieties in front of my eyes on paper. I can go back and forth, and mark things, then leave the catalog for a few days, think about things, go back and choose and mark something else and so on until I am set on my selection.

You can order a free catalog through the company’s site. They usually arrive somewhere at the beginning of January and you have a few weeks to make your selection and place your order. The tree will most likely ship in the spring right after they dig it and in a time that you can plant it.

I know the business of selecting fruit trees might be a bit overwhelming but I hope that I made it a bit clearer. It’s so important that you take the time to learn what you’re doing when it comes to selecting your trees because no one wants to wait three years and then get no fruit at all.

Remember that you can always pick up the phone and call the nurseries and talk to someone who can help you make the right selection. Or consult with your local cooperative extension agent on the best varieties for your area.

Fruit is so precious, and taking the time to learn all this will be so worth it when you get to pick your own fruit! If you have any experience with selecting fruit trees please share it with us in the comments below!

Hi! I’m Lady Lee. I help homesteaders simplify their homesteading journey while still producing a ton of food! I am a single mother of four, I was born in Israel and raised in an agricultural commune called a Kibbutz. Now I homestead in central NC.

Thank you for such detailed information.

You are welcome!

Thanks! Great info!

Happy it was helpful! Thanks for stopping by!